- | 8:00 am

An anthropologist explains why we need a universal language when talking about the metaverse

Norms set in the next few years are likely to structure the metaverse for decades. But first we all need common conceptual ground.

Quick, define the word “metaverse.”

Coined in 1992 by science-fiction author Neal Stephenson, the relatively obscure term exploded in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly after Facebook rebranded as Meta in October 2021. There are now myriad articles on the metaverse, and thousands of companies have invested in its development. Citigroup has estimated that by 2030, the metaverse could be a $13 trillion market, with 5 billion users.

From climate change to global connection and disability access to pandemic response, the metaverse has incredible potential. Gatherings in virtual worlds have considerably lower carbon footprints than in-person gatherings. People spread all over the globe can gather together in virtual spaces. The metaverse can allow disabled people new forms of social participation through virtual entrepreneurship. And during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the metaverse not only provided people with ways to connect but also served as a place where, for instance, those sharing a small apartment could be alone.

No less monumental dangers exist as well, from surveillance and exploitation to disinformation and discrimination.

But discussing these benefits and threats remains difficult because of confusion about what “metaverse” actually means. As a professor of anthropology who has been researching the metaverse for almost 20 years, I know this confusion matters. The metaverse is at a virtual crossroads. Norms and standards set in the next few years are likely to structure the metaverse for decades. But without a common conceptual ground, people cannot even debate these norms and standards.

Unable to distinguish innovation from hype, people can do little more than talk past one another. This leaves powerful companies like Meta to literally set the terms for their own commercial interests. For example, Nick Clegg, former deputy prime minister of the U.K. and now president of global affairs at Meta, attempted to control the narrative with the May 2022 essay, “Making the Metaverse.”

CATEGORICAL PROTOTYPES

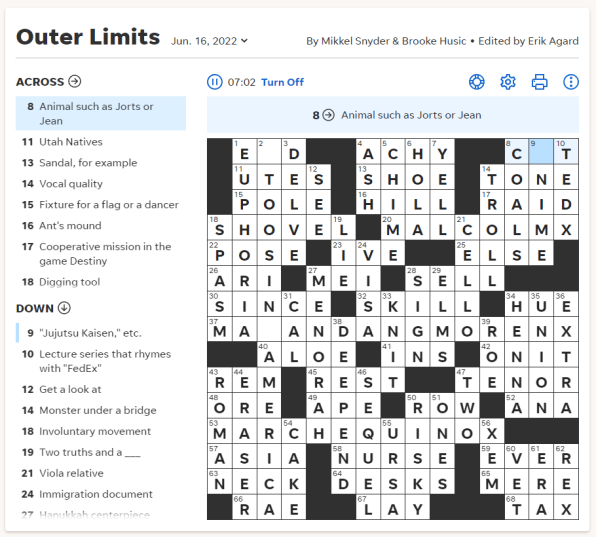

Most attempted definitions for metaverse include a bewildering laundry list of technologies and principles, but always included are virtual worlds— places online where real people interact in real time. Thousands of virtual worlds already exist, some gaming oriented, like Fortnite and Roblox, others more open-ended, like Minecraft and Animal Crossing: New Horizons.

Beyond virtual worlds, the list of metaverse technologies typically includes avatars, nonplayer characters and bots; virtual reality; cryptocurrency, blockchain, and non-fungible tokens; social networks from Facebook and Twitter to Discord and Slack; and mobile devices like phones and augmented reality interfaces. Often included as well are principles like interoperability—the idea that identities, friendship networks, and digital items like avatar clothes should be capable of moving between virtual worlds.

The problem is that humans don’t categorize by laundry lists. Instead, decades of research in cognitive science have shown that most categories are “radial,” with a central prototype. One could define “bird” in terms of a laundry list of traits: has wings, flies, and so on. But the prototypical bird for North Americans looks something like a sparrow. Hummingbirds and ducks are further from this prototype. Further still are flamingos and penguins. Yet all are birds, radiating out from the socially specific prototype. Someone living near the Antarctic might place penguins closer to the center.

Human creations are usually radial categories as well. If asked to draw a chair, few people would draw a dentist chair or beanbag chair.

The metaverse is a human creation, and the most important step to defining it is to realize it’s a radial category. Virtual worlds are prototypical for the metaverse. Other elements of the laundry list radiate outward and won’t appear in all cases. And what’s involved will be socially specific. It will look different in Alaska than it will in Addis Ababa, or when at work versus at a family gathering.

WHOSE IDEA OF ESSENTIAL?

This matters because one of the most insidious rhetorical moves currently underway is to assert that some optional aspect of the metaverse is prototypical. For instance, many pundits define the metaverse as based on blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies. But many existing virtual worlds use means other than blockchain for confirming ownership of digital assets. Many use national currencies like the U.S. dollar, or metaverse currencies pegged to a national currency.

Another such rhetorical move appears when Clegg uses an image of a building with a foundation and two floors to argue not only that interoperability will be part of “the foundations of the building” but that it’s “the common theme across these floors.”

But Clegg’s warning that “without a significant degree of interoperability baked into each floor, the metaverse will become fragmented” ignores how interoperability isn’t prototypical for the metaverse. In many cases, fragmentation is desirable. I might not want the same identity in two different virtual worlds, or on Facebook and an online game.

This raises the question of why Meta—and many pundits—are fixated on interoperability. Left unsaid in Clegg’s essay is the “foundation” of Meta’s profit model: tracking users across the metaverse to target advertising and potentially sell digital goods with maximum effectiveness. Recognizing “metaverse” as a radial category reveals that Clegg’s claim about interoperability isn’t a statement of fact. It’s an attempt to render Meta’s surveillance capitalism prototypical, the foundation of the metaverse. It doesn’t have to be.

LOCKING IN DEFINITIONS

This example illustrates how defining the metaverse isn’t an empty intellectual exercise. It’s the conceptual work that will fundamentally shape design, policy, profit, community, and the digital future.

Clegg’s essay concludes optimistically that “time is on our side” because many metaverse technologies won’t be fully realized for a decade or more. But as the VR pioneer Jaron Lanier has noted, when definitions about digital technology get locked in they become difficult to dislodge. They become digital common sense.

Also, read what will the metaverse actually look like in 5 years? This studio may have cracked it here.

With regard to the definitions that will be the true foundation of the metaverse, time is emphatically not on our side. I believe that now is the time to debate how the metaverse will be defined—because these definitions are very likely to become our digital realities.

Read more related tech articles in our tech section here.