Editor’s Note: This article is part of Fast Company Spark, a new initiative for middle and high school readers.

Penguins have a horrible smell. They excrete bodily fluids, which interact with bacteria, and the result is, well, pungent. In fact, nearly 3% of the ice in Antarctic glaciers is penguin urine. Since the temperature in Antarctica is well below freezing, the urine freezes in the ice immediately and can’t get washed off or evaporate.

Craig Cary has had a lot of experience with smelly penguins. He is the primary chair of the Antarctic Near-shore and Terrestrial Observation System (ANTOS) and a professor at Waikato University in New Zealand. Over the span of 26 deployments to Antarctica, he’s interacted with many penguin colonies with almost 1 million birds. He says that while they are incredibly cute, they are also aggressive and noisy. During a few weeks in December, the sun doesn’t set in Antarctica–and the penguins don’t sleep. As a result, they chatter relentlessly, making them especially difficult to work near.

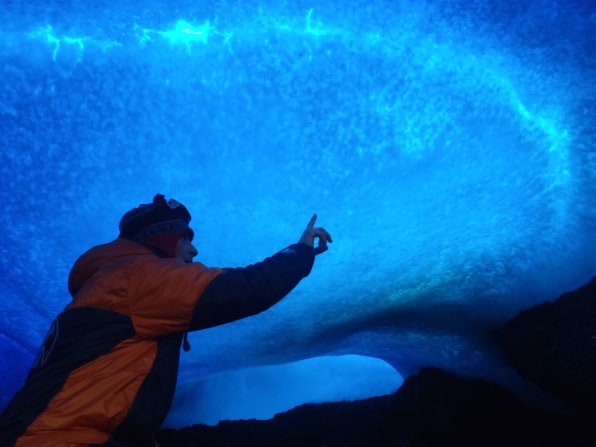

Mount Erebus bacteria sampling [Photo: courtesy Dr. Craig Cary]

HOW DO YOU GET SUCH A COOL JOB?

Cary’s interest in marine biology started when he was a young teen working at an aquarium in London, studying marine animals and later researching microbiology at Cambridge University. From there, he moved to the U.S. to study marine biology at the Florida Institute of Biology. He then won the Our World Underwater (OWU) scholarship, and was fully funded to travel around the world and meet top scientists, underwater photographers, geologists, and biologists. “The OWU scholarship completely changed my career direction,” he says. “Before getting the award, I had no intention of going back to university to get a higher degree. The experiences I got during that year showed me what I wanted to do.”

[Photo: courtesy Dr. Craig Cary]

Cary’s work is primarily focused on studying such bacteria in harsh environments, like deep-sea thermal vents and the soils of Antarctica. In 2001, he visited the University of Waikato in New Zealand, on a one-year sabbatical from his position at the University of Delaware. From there, he made his first trip to Antarctica and realized that it was a “gold mine for potential research.”

Massive camera for bacteria [Photo: courtesy Dr. Craig Cary]

In 2003, Cary accepted a position at the University of Waikato, and started his research on microbiology there. He is now the primary chair of the ANTOS steering committee consisting of 14 scientists and students. His team is made up of an administrative assistant, technical advisor, a data management team, physical science representatives, and Antarctic permafrost and soils (ANTPAS) representatives.

In November 2022, which is the summer season for Antarctica, he and his team will be searching for common bacteria by drilling holes in Mount Erebus, the southernmost active volcano on Earth. Common bacteria are found all over Earth, but Mount Erebus erupts routinely, and is completely surrounded by ice and desolate stretches of land. If they find common bacteria, it will indicate the flow of bacteria throughout the world. Bacteria fight, survive, and die by the trillion every moment, everywhere. As scientists discover more about these organisms, it’s clear that bacteria have a huge impact on our future and can even hint at Earth’s past.

WHAT’S IT REALLY LIKE TO BE A CLIMATE RESEARCHER IN ANTARCTICA?

When Cary is deployed in Antarctica, his team is prepping, packing, and testing equipment. In such barren conditions, safety is always the first priority. They are packing meals, checking insulation, and monitoring their body health. When they’re out on the terrain, they live in thick tents, cook on camp stoves, and try to avoid the penguins. Every day, they visit a given location and collect data. But, he says, “the weather can get really bad, without warning. We have to be prepared for everything.”

Collecting data — temperature sensors [Photo: courtesy Dr. Craig Cary]

But every time he returns to Antarctica, the blinding beauty takes him back to his first trip there. “The challenge of working in such extreme conditions pushes me personally and professionally,” he says. He wouldn’t change his career for anything–despite the smelly penguins and frostbite.