In January 2020, Luke Jerram got a foreboding phone call. Duke University was researching a new virus called SARS-CoV-2, and wanted to commission the artist to create a glass sculpture of the cell to reflect their research. About 2 million times larger than the actual virus, the sculpture was completed in March 2020 and went on to be featured on magazine covers around the world.

[Photo: courtesy Luke Jerram]

Jerram is known for his stunningly realistic, scientifically accurate sculptures of the moon, which have toured museums around the world. Some people may also know him from his ‘Play me, I’m Yours’ initiative, which brought over 2,000 pianos to streets, parks, and airports around the world (and kept me busy during many delayed flights). But since 2004, the British artist has also been busy designing meticulously accurate sculptures of viruses and bacteria, some deadlier than others.

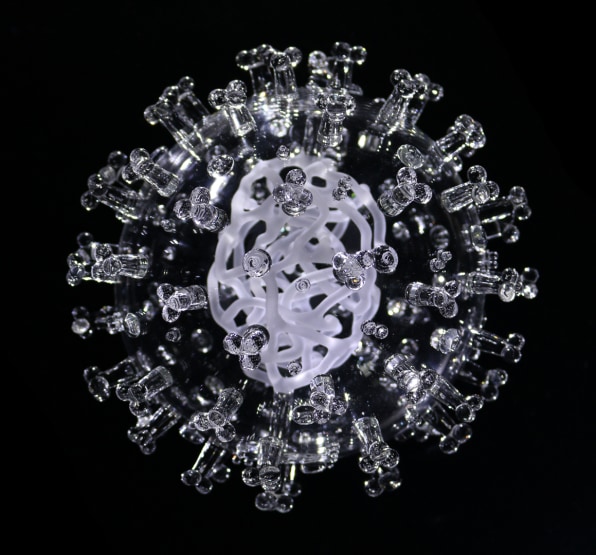

COVID-19 [Photo: courtesy Luke Jerram]

Titled Glass Microbiology, his series includes about 100 sculptures of more than 15 microbes from smallpox to ebola to the swine flu. Perhaps the most photogenic and fragile piece of science communication ever created, his sculpture of the COVID-19 virus helped the public visualize – and better understand —a disease that has now killed more than 6 million people.

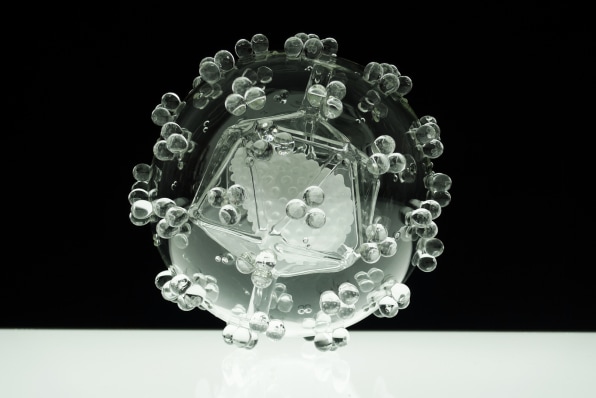

Avian Flu, Series 2 [Photo: courtesy Luke Jerram]

Jerram’s fascination with the sciences started at a young age, but he went on to study art at Cardiff Metropolitan University. “I’ve always been fascinated by how the world works,” he says. “As a kid, I’d take apart a radio or TV to see what’s inside.”

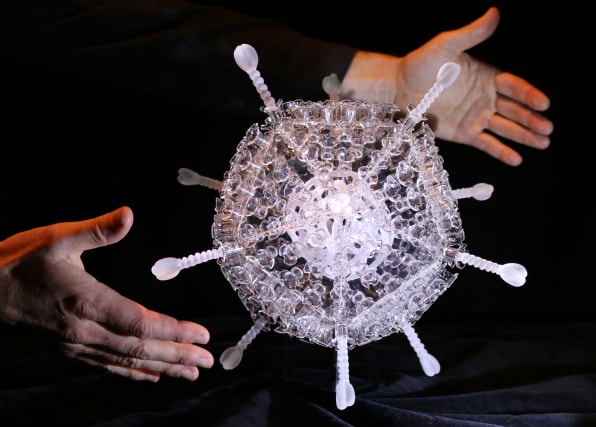

HIV [Photo: courtesy Luke Jerram]

The ‘Glass Microbiology’ series started with a sculpture of the HIV cell, which he created in 2004. He says the idea came to him from looking at images of viruses in newspapers. “They were all brightly colored, but viruses don’t have color,” he says. “Color gets added for emotional reasons.” So Jerram set out to create an accurate 3D representation of the virus. He chose glass for its transparency, but also because of the contrasting feelings it conjures. “You can create tension between the beauty of the object and what it represents,” he says.

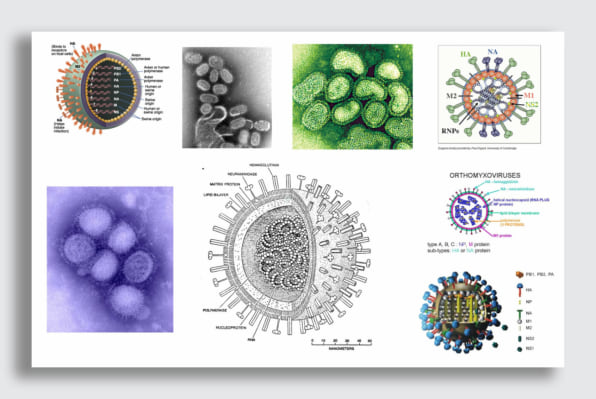

[Images: courtesy Luke Jerram]

To make the piece, Jerram starts by collecting scientific diagrams and called electron microscope images from a special type of microscope. He then translates that information into a set of technical drawings that is “as scientifically accurate as possible,” he says.

He then takes the drawings to a team of scientific glassblowers (a more accurate term here is “lampworkers”) who create the sculptures using borosilicate glass, the material test tubes are made of. Unlike traditional glassblowing, which starts with molten glass, lampworkers start with cold borosilicate glass that is melted over a flame, then stretched and shaped with incredible accuracy.

Oxford AstraZeneca Vaccine [Photo: courtesy Luke Jerram]

Jerram’s last sculpture illustrates a nanoparticle of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. Here’s hoping it remains the last sculpture in the series for a long, long time.