- | 1:00 am

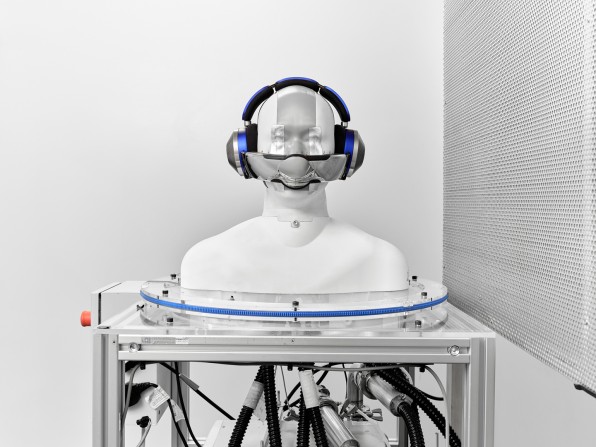

Dyson’s futuristic new headphones double as an air purifier for your face

Six years ago, mask mandates and a global pandemic were beyond the public’s imagination. And yet Dyson began development of a new product all the same. It was a wearable air purifier, necessitating an oxygen mask and a backpack. Some 500 prototypes later, the company is announcing the Dyson Zone. It will be out this fall for an unspecified price.

It’s still a wearable air purifier, but the backpack is gone. Now the machinery is hidden inside a pair of chunky cup headphones, which channel filtered air into a visor that sits over your nose and mouth. Stuffed full of noise-canceling technology, the device allows you to listen to music or even take calls while breathing clean air; it filters 99% of particles down to 0.1 microns, which means the Zone is capable of filtering dust and bacteria. Dyson’s own testing has found it’s even “pretty effective” at removing viruses like the coronavirus, according to Tom Bennett, head of product development with a focus on wearables.

[Image: Dyson]

“But we’re quite careful that we need to be sensitive about this,” Bennett clarifies. “We haven’t designed this product to protect from coronavirus.”

The problem of air pollution has been a point of interest for founder James Dyson for decades. Back in 1998, right as we learned that Chinese cities lived under a constant fog but before forest fires were a seasonal oppressor across California, Dyson released a cyclone filter that could be stuck on diesel exhausts to capture 95% of particulate matter from combustion engines. But like a vacuum, it had to be cleaned and emptied regularly, so it never wooed the delivery and transportation industry. After that, Dyson spent $700 million to develop his own electric car. But the car was prohibitively expensive to produce, especially since he couldn’t get a single major auto manufacturer interested in it.

So 25 years after creating his exhaust cyclone, Dyson is challenging urban pollution again. But this time, instead of preventing pollution at its source, the company has developed a way to live with it. That’s the unavoidable, dystopian truth behind the Zone: It’s an absurdist solution for absurdist times—and yet, it’s also an ingeniously constructed Rube Goldberg contraption for your face, built to protect you from a world that’s growing too poisonous to inhabit without consequence.

[Photo: Dyson]

HOW DO YOU SQUEEZE AN AIR FILTER INTO HEADPHONES?

Headphones were never the initial focus for Dyson, as the firm looked at just about every way you might wear an air filter on your body.

“We set about exploring all the options . . . shoulder-mounted, neck-mounted, top-of-the head-mounted, but without the headphones. We like to go broad initially to make sure we settle on the right concept,” Bennett says. “Headphones, we settled on, as they are such a natural, known way of wearing a device . . . also [with] the weight distribution and center of gravity, the product is really stable on your head.’”

The team at Dyson compares headphones to a horse’s saddle, capable of distributing weight across a larger surface. And that’s important, as these headphones aren’t mostly hollow like many on the market, but packed with large batteries and mechanics.

[Photo: Dyson]

Those mechanics start with the ear cups, each of which house a motor and a filter that looks straight out of a Dyson vacuum (the filter can last for about a year of daily use). The filter is designed much like an N95 mask, as it uses static electricity to pull small particles toward it to improve its filtration efficiency. Meanwhile, an extra carbon filter captures gases like CO2 and ozone.

Once filtered, the air shoots from the ear cups through the visor, a rubbery mask that sits in front of your mouth and nose. On our call, Bennett holds this visor up to his camera, bending and twisting it in his hands. You can wear the headphones completely on their own simply to listen to music, without air filtering. But the visor attaches to the ear cups with a magnet so that you can start filtering in all of a second.

[Photo: Dyson]

The ear cups conform to the shape and size of your head, and you can bend the visor to fit your face accordingly. Notably, however, the visor doesn’t press flush against your cheeks like an N95 mask. It floats for comfort.

As the air pumps toward your nose, a mesh cover on the visor softens the flow so that the experience feels less like you’re breathing from a hair dryer than your own personal pocket of air. “That’s the clever bit,” Bennett says. “Without that [mesh] you don’t create that bubble.” The personal air bubble is so resilient that Dyson proved it works even in crosswind.

All of these motors and air channels create noise, so another reason Dyson engineers liked the idea of building headphones was that they could use active noise cancellation to silence any sounds that couldn’t be eliminated mechanically. For this task, the headphones actually feature five processors. They also have a pair of microphones for taking voice calls; they analyze your speech to cut out background noise as you talk, allowing you to take calls even while the air filter is running.

As for the batteries, those live in the headband as two of the padded “pods” you see in the design. They provide a still-unspecified amount of run time for the Zone. Comparable headphones of this size can easily offer 24 hours of operation, but a Dyson Animal hand vacuum maxes out around 40 minutes. Needless to say, you can expect the Zone to fall somewhere between these two extremes.

[Photo: Dyson]

WHAT SHOULD A WEARABLE LOOK LIKE?

One point Bennett makes clear on our call is that user comfort was of paramount importance, and the company sees that core comfort as the Zone’s big advantage over disposable masks. “We treat wearables, like the Dyson Zone, the same as every other product we make,” Bennett says. “It’s always function first.”

But he also concedes that any wearable becomes part of our personal expression. Rather than attempting to create a new aesthetic for the Zone, Dyson designed its first wearable with the familiar tropes of its own design language: as something unabashedly machine-like, with bright colors calling attention to its mechanical innovations. Anodized aluminum ear cups feature the sort of venting holes you might see on an Apple desktop computer. Let’s not mince words: Dyson has ostensibly designed a Dyson vacuum that goes on your head.

“It is bold. It is unashamedly bold. We made a point of that with the metallic finish,” Bennett says. “You’re going to make a statement anyway, so make a bold statement. The statement you’re making is, ‘I’m enjoying my city and protecting myself from the pollution that’s around me.’”

That’s a statement that not everyone will want to make. I find myself torn between wondering who would possibly don this Dyson helmet, and knowing that if the last two years have taught us anything, it’s that a large part of the population will wear just about anything to stay safe. But will the Zone be popular or parodied? I have no idea.

“To an extent, neither do we,” Bennett admits. “But our aim, and what we’ve done, is find the problem, develop the solution, and then explain it. I think people will get it.”