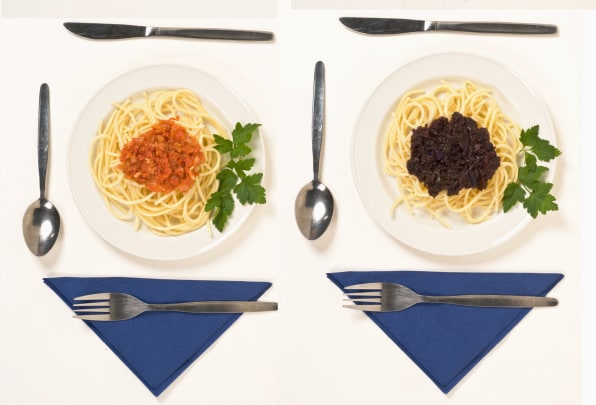

Fifteen years ago, in the middle of winter, Cathie Martin was impatiently waiting for her tomatoes to ripen. The John Innes Centre botanist already knew what was going to happen: Their green skin was about to turn a miraculous purple. She’d swapped out a few genes to supercharge their anthocyanin content—the same vibrant antioxidants that give blueberries and blackberries their rich color.

[Photo: courtesy Cathie Martin]

Now, assuming the U.S. Department of Agriculture approves their sale in the coming weeks, Martin’s tomatoes could be available for the first time—as seeds you can grow or fruit you can buy at the store. But it’s also a significant moment to reframe the way we think about genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in produce—not merely as a means to cut costs for Big Agriculture but as an opportunity to take an object that nature gave us and improve upon it, much as we would a smartphone or pair of sneakers.

[Photo: courtesy Cathie Martin]

“One [visual] trait I like very much comes from what are currently known as yellow tomatoes,” Martin says. “When the purple is mixed in, it’s a fantastic, more indigo color, a kind of bluer purple. If you were to make a bloody Mary, it would be a royal blue Bloody Mary.”

[Photo: courtesy Cathie Martin]

Today, GMOs are common in the American diet, but they’ve largely been crafted for corporate profit rather than consumer desire. By last count, 94% of soybeans, 94% of cotton, 92% of corn, and 95% of canola planted in the U.S. are GMO strains. The genetic tweaks improve yield and resist disease. They end up in oils, clothing, processed foods, and livestock. Some 95% of animals that provide meat and dairy in the U.S. eat GMO crops.

Beyond that, however, the list of bioengineered whole fruits and veggies approved for sale in the U.S. is scant. Monsanto, and the frozen french fry company Simplot, have created their own potatoes. Others have crafted a squash, papaya, and eggplant—all focused on resisting disease or pests. That’s it, with one exception: The Pinkglow pineapple by Del Monte Fresh. Approved for sale in 2020, Del Monte sells the product as a premium direct-to-consumer brand. You can order a single pink pineapple for your valentine for $40.

But Martin has little interest in controlling any genetic or brand IP, like Monsanto or Del Monte. In fact, her company, Norfolk Plant Sciences—founded in the U.K. alongside her colleague Jonathan Jones—leans closer to Iowa’s hippy nonprofit Seed Savers Exchange than a global agriculture powerhouse. As a botanist, she first studied how to use genetics to boost the anthocyanin content in tobacco plants. The problem was that anthocyanin production worked its way into the entire plant—including the leaves and the stem—which wasted energy and stunted its growth. With her tomatoes, Martin isolated how to increase anthocyanin solely within the fruit itself, and only when the fruit was at its natural ripening state. So these tomato plants can grow under the same conditions, and with the same yield, as conventional options.

[Photo: courtesy Cathie Martin]

Now she imagines a surprising way forward with her tomatoes. She will give them to the market however the market wants to consume them. That means she’ll sell you the seeds to grow them yourself. She’ll allow farmers to grow them and sell them to stores to sell to you. She’ll even turn a blind eye on you cross-pollinating these purple tomatoes with another variety in your garden. Martin isn’t protective of her product; she just wants to see it grow.“It’s just a different business model. I think we very much want to grow it in response to consumer demand. The big danger with this type of thing is it’s just a boutique thing that comes, passes, and no one is interested anymore. But sometimes you get a change, a new food, and it really works. And it brings consumer satisfaction,” Martin says. “For example, 20 years ago, if you bought salad leaves in the supermarket, they would be green iceberg. Now . . . it’s all different colors. And people love the idea of color in salads. I would like our tomatoes [to work] similarly.”

For two years, Martin has been seeking USDA approval for her product, providing the exact genetic details (three genes were swapped in her plants, sourced from snapdragon and thale cress) and nutritional data. More recently, the USDA has promised to work much faster at approving GMOs, capping analyses to 180 days. While the deadline has already passed, Martin is confident the tomatoes will be approved or rejected by the end of March or April.

“I don’t want to preempt the decision on that,” Martin says, “but we’re optimistic that this should not be regulated because there’s nothing inherently dangerous environmentally or for health in these tomatoes.”

Longer term, Martin suggests that her tomatoes don’t need to be the only fruit with boosted anthocyanin content. In 2013, researchers debuted an apple loaded with the compound, so much so that it resembles a red-fleshed plum, and Martin believes the same is possible with bananas, oranges, and countless other fruits.